African Penis Enlargement

African Penis Enlargement: The Ancient Ritual of the Batammariba

Long before the Western world introduced surgical procedures and commercial products for penis enlargement, the Batammariba people—also known as the Somba of Togo and Benin—had already mastered the traditional art of African penis enlargement. This ritual practice, focused on the enlargement and elongation of the male organ, was a required part of a boy’s initiation into manhood.

Living in the mountainous regions of West Africa, the Batammariba (Somba) are recognized for their striking mud tower homes and deep-rooted cultural customs. In Togo, they inhabit the northeastern Kara region, where they live alongside the Kabye—the second largest ethnic group in the country.

Living in the mountainous regions of West Africa, the Batammariba (Somba) are recognized for their striking mud tower homes and deep-rooted cultural customs. In Togo, they inhabit the northeastern Kara region, where they live alongside the Kabye—the second largest ethnic group in the country.

Across the border in Benin, where they are referred to as Somba, they reside around the Atakora mountain range in the northwest. There, they share land and cultural similarities with their northern neighbors, the Gur people of Burkina Faso, who also hold a rich tradition in both architecture and ceremonial practices.

The Batammariba’s initiation rites—especially their techniques for African penis enlargement—are a powerful example of how indigenous knowledge and identity were tied closely to physical development, status, and adulthood.Rituals of

African Penis Enlargement Among the Batammariba

Among the Batammariba, the journey into manhood is marked by a deeply symbolic and physical transformation. The preparation for male initiation begins with the village herbalist, who carefully pounds and mixes traditional herbs into a powerful blend. These herbs, passed down through generations, are central to the practice of African penis enlargement—a sacred rite tied to masculinity and readiness for adult life.

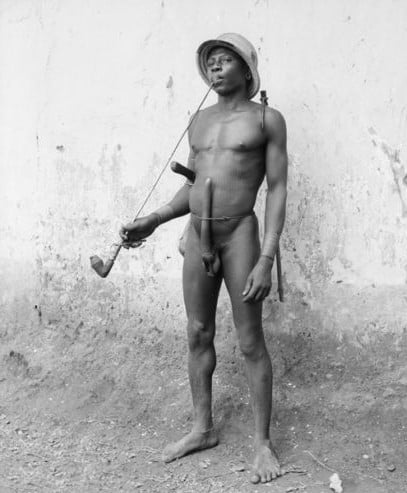

Once the herbal mixture is prepared, it is gently applied to the initiate’s penis. A hole is then crafted—either in a tree branch or a piece of ivory—into which the initiate places his penis. It remains there for several months, with the belief that this process stimulates growth and elongation. This stage is both physical and symbolic, marking the boy’s transition from youth into the responsibilities of manhood.

At the conclusion of this rite, the initiates are honored in a public ceremony. They wear extravagant garments draped over their shoulders, with cowrie shells adorning their necks and waists—symbols of fertility, wealth, and status. Their heads are crowned with traditional horned headdresses, completing their transformation.

Oral tradition suggests that such African penis enlargement practices were once widespread across the continent. For centuries, they were considered a normal and respected part of cultural identity. However, the arrival of Islam and Christianity brought sharp opposition. Colonizers and missionaries labeled these indigenous rites immoral and, in many cases, banned them under threat of death or enslavement. What was once sacred was suppressed, leaving only traces in oral memory.

Yet among the Batammariba, echoes of this ancient practice remain—a testament to a time when the body, spirit, and community were shaped together through ritual and tradition.

Spirituality Of African Penis Enlargement

Beyond Ego: The Sacred Meaning of African Penis Enlargement

To outsiders, the African penis enlargement ritual of the Batammariba (Somba) may appear egotistical or self-absorbed. But a deeper look reveals that this ancient practice serves a far greater purpose. Among these people, penis enlargement is not just about the individual—it supports the cohesion of the community and nurtures its spiritual health.

In the physical realm, the Somba believe that a larger penis enhances procreation. They hold that greater size leads to greater pleasure for the woman, resulting in more frequent orgasms and, ultimately, more children. Through generations of observation, they’ve noted a pattern: women who experience more orgasms tend to bear more children, and men who father many children often have larger sexual organs.

Some may dismiss this belief as superstition, but scientific research lends some support to it. Studies suggest that female orgasm may increase sperm retention and, by extension, the likelihood of conception. In this light, the Batammariba’s assumptions reflect not ignorance, but an intuitive grasp of reproductive mechanics passed down over centuries.

Yet for the Batammariba, African penis enlargement is about more than reproduction—it is a sacred act of spiritual alignment.

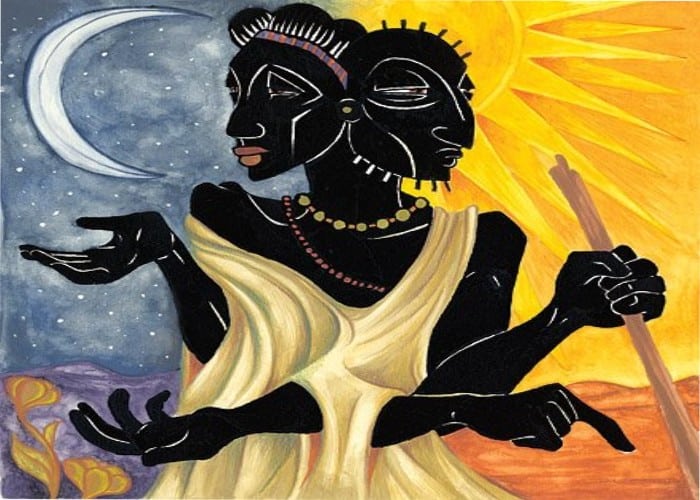

Their cosmology teaches that the universe is built upon two fundamental forces: masculine and feminine energy. These energies are not just opposites—they are necessary counterparts. When in balance, they produce harmony, creation, and life. When separated or misaligned, they create chaos and destruction.

This spiritual philosophy is embodied in the androgynous deity Kuiye, the supreme being who is both male and female. Kuiye represents the perfect union of these energies, a state the initiates strive to embody through ritual.

To enlarge the penis is, symbolically, to strengthen the masculine force. Not for dominance, but for the purpose of tethering the feminine energy, which can be wild, fluid, and untethered by nature. Without this anchoring, the Batammariba believe, the feminine energy may drift, breaking the sacred union and unleashing disorder into the world.

Therefore, the male who conquers and binds the feminine—not through force, but through sacred union—becomes more than a man. He reflects Kuiye. He channels divine balance. He becomes, in essence, a demigod.

God Kuiye

Kuiye: The Androgynous Creator of Gods and Men

Kuiye, the supreme deity of the Batammariba, is both the creator of the gods and the originator of humankind. Though described in human terms, Kuiye is neither solely male nor female, but both. This dual nature is why the deity is often referred to as both “Our Father the Sun” and “Our Mother.”

According to Batammariba cosmology, Kuiye exists in two distinct yet inseparable forms. The physical form, called Kuiye (masculine), is believed to dwell in the sun village—a sacred realm in the west, beyond the sky. The spiritual form, known as Liye (feminine), is more familiar to human eyes: it appears daily as the radiant disc of light that crosses the heavens.

Together, Kuiye and Liye represent the full balance of divine energy—visible and invisible, male and female, matter and spirit—guiding both gods and mortals through the cycle of life and light.

.

The Great Home Builders

The Sacred Architecture of the Batammariba: Builders of Balance

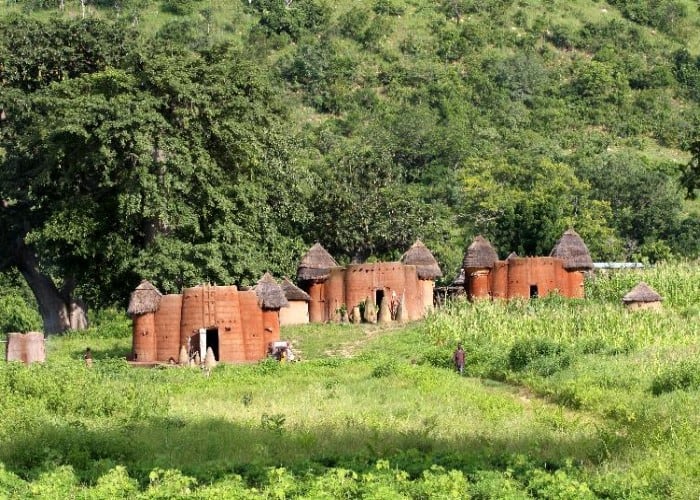

The Batammariba are best known for their extraordinary building skills and architectural genius. In fact, the ancient meaning of the name Batammariba is said to be “the great home builders of the earth.” Even colonial administrators acknowledged their mastery, referring to them as Tamberma—a term meaning “good home builders.”

Travel to Koutammakou, the homeland of the Batammariba in northern Togo and Benin, and their reputation becomes undeniable. Rising from the earth are their signature Takienta tower-houses—impressive mud structures with two stories, thick sculpted walls, and either flat or conical thatched roofs.

These fortified homes, also known as Tata Somba, are more than shelter—they are reflections of spiritual harmony. The ground floor is used to house livestock at night and includes a fire pit built into the wall for cooking. The upper floor serves multiple purposes: a rooftop courtyard for drying grain, sleeping areas, and granaries for storing food.

Every detail of the Takienta is deliberate. The walls are decorated by the women of the household while the mud is still wet, inscribing symmetrical lines and spiritual motifs with their hands. The architecture isn’t just functional—it’s spiritual. Each home is built as a living symbol of masculine and feminine balance, with the contrast of light and shadow inside representing the dual energies that define Batammariba cosmology.

Just as they believe in the union of masculine and feminine in the body and the spirit, so too do they construct their homes in alignment with this universal principle. The house becomes a sacred space—protective yet nurturing, strong yet gentle, structured yet alive.

Among the Batammariba, architecture is more than engineering. It is ritual. It is identity. It is the material expression of their belief that harmony between opposites—light and dark, male and female, earth and sky—is the foundation of life itself.

Agro-Pastoralists

Livelihood and Legacy: The Agro-Pastoral Life of the Batammariba

With an estimated population of over 176,000, the Batammariba are believed to have migrated to their current homeland in northern Togo and Benin from the north and northwest regions around Burkina Faso. Historical accounts suggest they once lived alongside the Mossi people, eventually settling between the 16th and 18th centuries.

Traditionally agro-pastoralists, the Batammariba maintain a lifestyle deeply rooted in farming and livestock rearing. The wealth of a household is not measured in currency, but in animals—particularly cattle, goats, and sheep. Livestock is not just economic capital; it carries profound social and cultural significance.

According to researchers, approximately 52% of the animals owned by Somba households are reserved for funeral rites, 28% are used for dowries, and the remaining are sold for income or trade. This distribution reveals the central role animals play in upholding community traditions.

Funerals among the Batammariba are major communal events marked by deeply spiritual and symbolic acts. One such rite is the Tibenti, or the dance of drums, performed to honor and guide the spirits of the departed. Another central ritual is the “turning over” ceremony, conducted on the funeral house—a symbolic act of releasing the soul and completing the transition from the physical world.

In Batammariba society, livestock is not merely a sign of prosperity—it is a key that opens the way to marriage, memory, and the afterlife. Through their animals, they honor ancestors, uphold family ties, and express the rhythms of life and death that shape their world.

Importance Of Cowrie Shells

The Sacred Symbolism of Cowrie Shells Among the Batammariba

In Batammariba tradition, cowrie shells are more than decoration—they are sacred symbols woven into the spiritual and social fabric of life. At funerals, cowries are carefully placed around the entrance of the funeral house, just as novices are adorned with cowries around their waists and necks during rites of passage. Above the doorway, earthen horns are placed on the roof, echoing the horned headdresses worn by initiates.

Cowries hold deep significance in Batammariba cosmology. These small, gleaming shells appear in the most important ceremonies—funerals, initiation into adulthood, and even African penis enlargement rituals. Their presence signals transformation, reverence, and the passing of sacred knowledge.

Part of the reason for their symbolic weight lies in their form. The shape of the cowrie shell closely resembles the female genitalia, and as such, the Batammariba regard it as a representation of the womb’s life-giving energy. It is a feminine symbol—creative, fertile, and protective. To wear or display cowries is to invoke the presence of the feminine force, which balances and empowers both male and female rites.

Whether marking the doorway to the spirit world or encircling the bodies of the living, cowries carry meaning. They are silent prayers for fertility, safe passage, strength, and spiritual harmony—a small but powerful reminder that in Batammariba life, beauty and symbolism are never far apart.